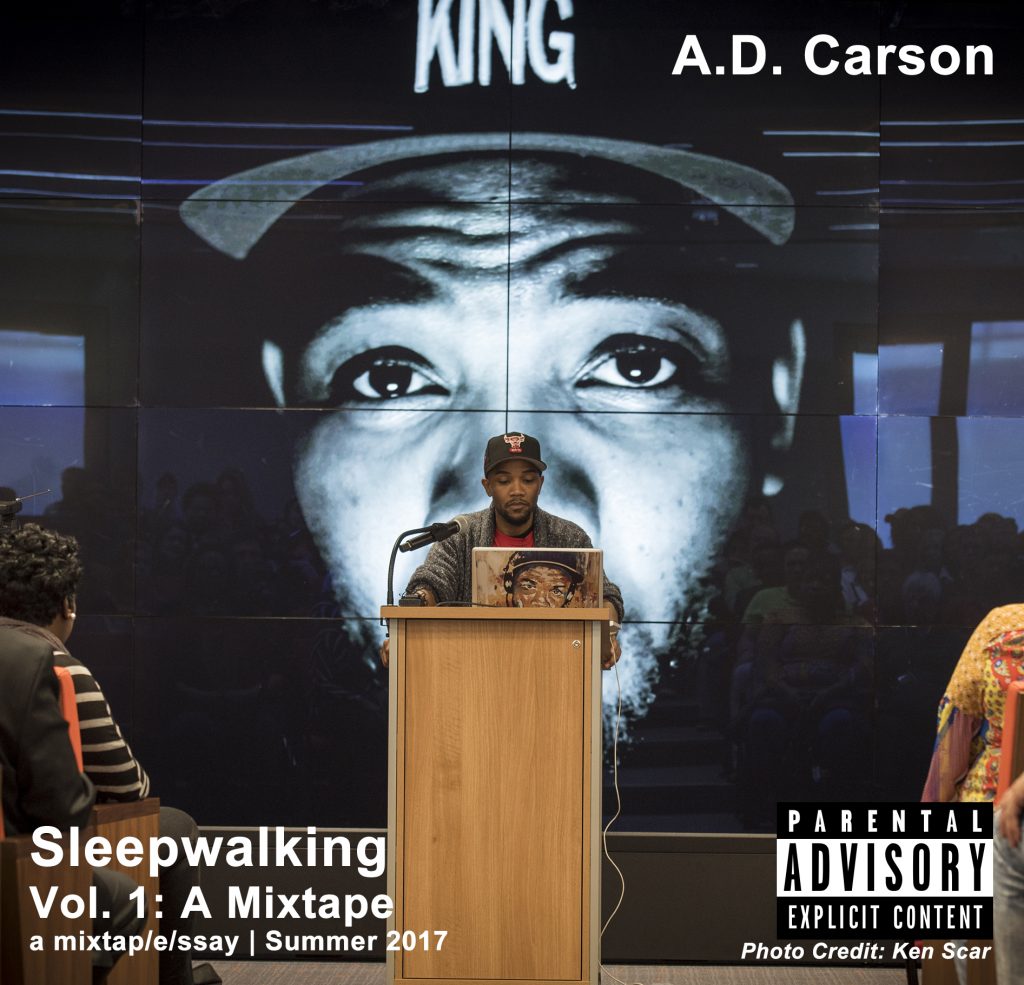

About Sleepwalking, Vol. 1

“Peace to y’all.” seems an appropriate greeting to the those gathered on the early August morning at McGuffey Park in Charlottesville, VA.

We have just marched from the Jefferson School to the park, where there is a rally to make clear the plan for the day—stand against white supremacy. I was asked by one of the organizers to deliver some words. I have been recently appointed Assistant Professor of Hip-Hop at the University of Virginia, and my work speaks to issues like those of the day, so he thinks it makes sense that I say something.

The audience returns my greeting and welcomes me with applause as I try to rearticulate words I had delivered just months earlier in the presence of my dissertation committee and the capacity audience in front of which I defended the rap album and digital archive I had submitted to receive my PhD. I, first, echo the sentiments of Vice-Mayor, Dr. Wes Bellamy, who spoke before me and quoted Martin Luther King, Jr.’s words, “Somebody told a lie one day.” I want to speak about that lie how it might be related to the people who have descended upon Charlottesville as a way of mourning – “a death…of America, or an America they envision,” and how that poor vision they have is referred to in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man.

I read:

“[Y]ou’re constantly being bumped against by those of poor vision. Or again, you often doubt if you really exist” [4]. The narrator continues, “You wonder whether you aren’t simply a phantom in other people’s minds. Say, a figure in a nightmare which the sleeper tries with all his strength to destroy. It’s when you feel like this that, out of resentment, you begin to bump people back” [4]. He later states: “I remember that I am invisible and walk softly so as not to awaken the sleeping ones. Sometimes it is best not to awaken them; there are few things in the world as dangerous as sleepwalkers. I learned in time though that it is possible to carry on a fight against them without their realizing it” [5].

I go on to read more words from my dissertation – the quote from which James Baldwin takes the name of his book, “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, / No more water, the fire next time” [278]. And then I read the poem, “Good Mourning, America,” which attempts to tie all the aforementioned thoughts together.

12 August 2017 will likely be remembered in this country because of the tragedy that unfolds in Charlottesville over the course of the day. The scenes surrounding the deaths and injuries will continue to be played on television as pundits opine about America’s future, and no doubt they’ll play over and over in the minds of the people who were there, standing face-to-face with white supremacist terrorists as a direct repudiation of their ideology and their plans for this city and this country. I’ll remember the day for those reasons, too, but also because it marks almost three months since the day I moved to town.

Two days before I moved to town, 13 May, there was a rally at the same downtown statue of Robert E. Lee. It made national news, and for good reason: most of the people assembled at the monument brought torches to the nighttime gathering, giving it the optics of a Klan meeting you might see in a documentary about how much this country has progressed. Instead, it was evidence of how untrue that might be. In July, I presented about the legacy of racist memorials and monuments at my [previous] southern American university at the Rhetoric Society of Europe conference I watched a live stream of the Klan rally held in Charlottesville on my computer in Barcelona. In August, on the eve of their “Unite the Right” rally, once again at the Lee statue, they white supremacists were back, with their torches, this time marching them across the campus, chanting hate, and ultimately violently clashing with a group students, staff, and faculty at the feet of the statue of Thomas Jefferson outside his Rotunda.

Just half an hour earlier I’d walked past that statue after being told the prayer service at St. Paul’s Memorial Church, across the street from The Rotunda, was full. I watched the mayhem via live stream. The next day, after my remarks at McGuffey Park, I joined my new colleagues and community at the counter-protest at the Lee statue.

From the May torches to the August torches – my first three months living in Charlottesville – I had lots of time to try to sort through my thoughts about my new home. Similar to my process as a doctoral student, I funneled the time and energy left from researching and discussing the issues into writing music and poetry in response. The responses contained in this project are more questions than anything else. But perhaps that’s me trying to dictate what they might be to anyone else, and I should resist the urge to do that.

I should also resist the urge to tell people I don’t believe Charlottesville is much different than many of the other places I lived before moving [Clemson, SC, and Springfield and Decatur, IL] so far as these summer events go. I don’t often resist this urge, though. The music and poetry I’ve written here in Charlottesville is unique to this place and time, and I think that’s important. I’m teaching “Writing Rap” at UVA this semester. The students who have listened to my dissertation asked if I will continue to make music while I’m here. In response, I told them I couldn’t imagine being here and not having music as an outlet with so much happening. My hope is that they’ll use what they’re learning in my class to ask some of their own questions.

My work hasn’t changed much from the time I graduated. Geography aside, there hasn’t been much time for any major changes. This latest project, for me, is a return [if there ever was a departure] to Ellison’s invisibility, back in that underground space, aspiring to a dopeness that might inspire a newly developed analytical way of listening, perhaps somewhere ahead, on, or behind the beat, waiting patiently for the other voices to speak. In a world in which being “woke” is an aspiration for many, sleepwalking, as Ellison describes it, seems inevitable. If this is true, then not only are there few things as dangerous as sleepwalkers, there are few times as dangerous as now. But, in my mind, the project isn’t so concerned with avoiding that danger than it is with living in its presence.

Contributing to what is now known as Sleepwalking Vol. 1 was a much different experience than the work we did on Owning My Masters. This was mainly due to the quick turnaround time in between the two projects. While music for Owning My Masters was collected over a period of years, Sleepwalking was put together over the course of a few weeks. So there was definitely pressure to meet or surpass what we did with the previous project. With Sleepwalking Vol. 1, the end result was a pretty concise but extremely layered body of work that I think will make just as much noise as the dissertation. If Owning My Masters was walking through a field of fire, Sleepwalking Vol. 1 is the active minefield you encounter immediately after coming out of the fire.

-Preme-

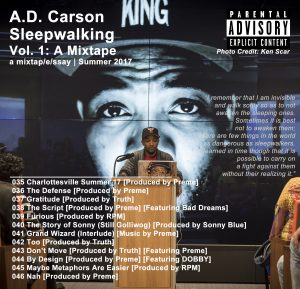

Sleepwalking, Vol. 1 features work with previous collaborators Preme, Truth, Bad Dreams, and Sonny Blue, as well as UVA Music doctoral student RPM, and Sydney, Australia-based rapper DOBBY. Preme and Truth contribute significantly to this project, as they did to my dissertation project with both rhymes and beats. They have been making beats and writing rhymes to document these realities since before I began my doctoral studies, and they continue to do so with and without me. The short time I’ve been in my new home has provided me the opportunity to meet and collaborate with many people who are doing similar work in language and music, and some of that work appears in this collection. The sources of material for our musical-lyrical examinations vary widely, and engage many conversations, from Donald Trump and the terrorist acts committed in his name to the perils of apathy, from patriotism to social paralysis, gentrification to Jay-Z’s “Story of O.J.,” metaphors to murder, and much more. I use the term “mixtap/e/ssay” to describe the projects that precede my dissertation, and I think it fits here, too. The first rap on the project begins, “This is kind of like the last thing – but, still, entirely different. / You don’t have to understand it. I still invite you to listen.”

Sleepwalking, Vol. 1 features work with previous collaborators Preme, Truth, Bad Dreams, and Sonny Blue, as well as UVA Music doctoral student RPM, and Sydney, Australia-based rapper DOBBY. Preme and Truth contribute significantly to this project, as they did to my dissertation project with both rhymes and beats. They have been making beats and writing rhymes to document these realities since before I began my doctoral studies, and they continue to do so with and without me. The short time I’ve been in my new home has provided me the opportunity to meet and collaborate with many people who are doing similar work in language and music, and some of that work appears in this collection. The sources of material for our musical-lyrical examinations vary widely, and engage many conversations, from Donald Trump and the terrorist acts committed in his name to the perils of apathy, from patriotism to social paralysis, gentrification to Jay-Z’s “Story of O.J.,” metaphors to murder, and much more. I use the term “mixtap/e/ssay” to describe the projects that precede my dissertation, and I think it fits here, too. The first rap on the project begins, “This is kind of like the last thing – but, still, entirely different. / You don’t have to understand it. I still invite you to listen.”

Waking up is hard to do, I imagine. I won’t even pretend this is intended to do that. It’s likely more akin to soft walking in an attempt to carry on a fight … or speaking on the lower frequencies.